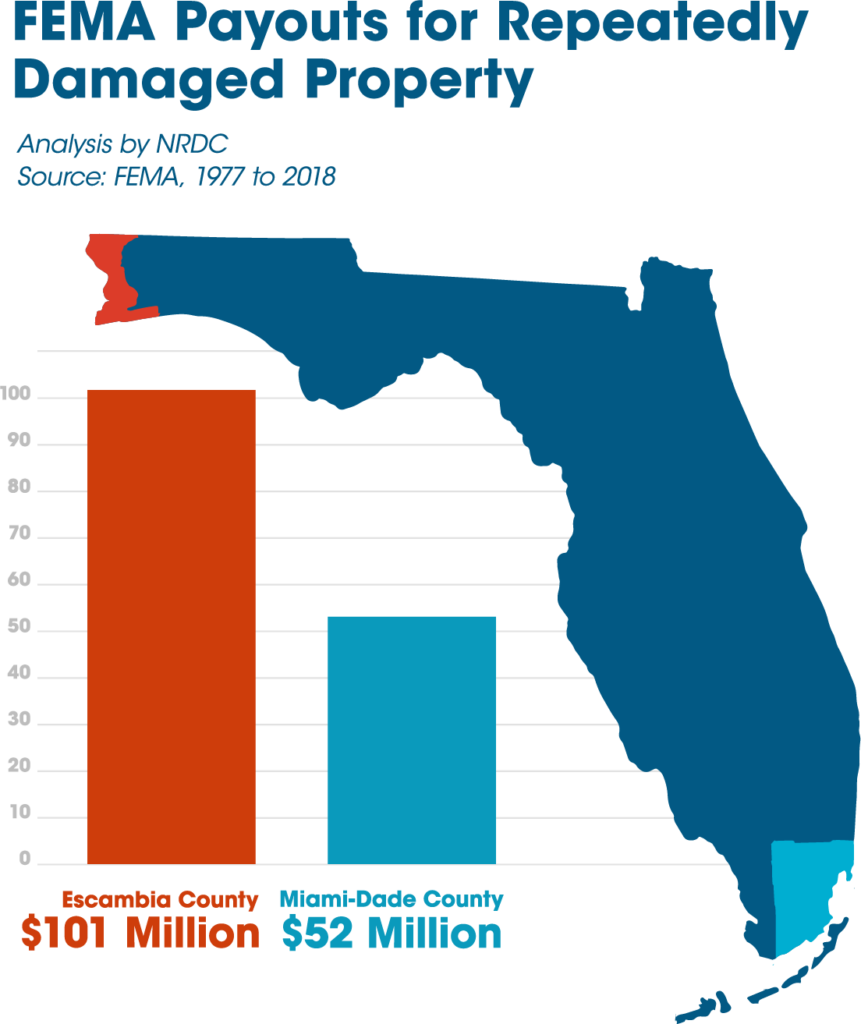

Escambia County sits at the northwest corner of Florida, near the Alabama state line. It has roughly one-tenth of the population of Miami-Dade County, which is its geographical bookend near the state’s southeastern tip, and is one-third its size in square miles. Unlike Miami, Escambia County doesn’t have a major league football, basketball or baseball team. But the conservative, Republican-dominated county, known for its emerald waters and pristine beaches, dwarfs Miami-Dade in one curious metric.

Escambia County accounts for nearly twice the dollar amount of claim payments made under the National Flood Insurance Program for properties that have been severely, repeatedly damaged by floods – $101 million to populous Miami-Dade’s $52 million. The county has a history of flooding. It and its county seat, Pensacola, were flooded in 2004 by Hurricane Ivan, a freak downpour in 2014 and last month by Hurricane Sally.

The flood insurance program, which stays afloat because of a $30 billion line of credit from taxpayers, is under pressure to avoid paying out flood claims to the same property over and over. Instead, it’s supposed to help communities and homeowners make their neighborhoods and houses more flood-resistant or, in some cases, buy out the homes so the flood-prone property can be used for public open space. But the flood insurance program, operated by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), is struggling to meet those goals.

Doug Underhill, one of Escambia’s five county commissioners, lives on Perdido Key, a barrier island that sits offshore from downtown Pensacola. On Sept. 16, Sally walloped Perdido Key, cutting channels right through it. Underhill’s waterfront home was built in 1973, he said, although he’s only owned and lived in it for the past nine years. The first floor of the house had been badly damaged by flooding in 2014. He got a letter from FEMA showing that the damages were valued at 67 percent of the value of the house, he said, adding that under the flood insurance program’s rules, he expected to be given a full payout and allowed to tear down his old house and rebuild it to current building and floodplain standards.

“For reasons that I cannot even begin to describe, FEMA refused to do so,” Commissioner Underhill told Flood Trends. Instead, he was given about $65,000 to repair the first-floor damage. FEMA “didn’t act according to its supposed own policies.”

When Hurricane Sally hit Perdido Key on its way to Pensacola, it twisted Underhill’s home off its foundation, he said. A boat broke loose from its boatlift and smashed a hole in his first floor, letting in seawater and undoing all of the repair work that had been done after the 2014 flooding.

“We’re hiring attorneys and public adjusters to ensure we don’t get jerked around again and actually build a home that is appropriate for Perdido Key going into the future,” said Underhill, a self-described libertarian Republican with a military background. This will be the 10th claim made against the flood insurance program by him or previous owners of the house, he said.

Congress created the National Flood Insurance Program in 1968 to provide affordable flood insurance to the public, saying it wasn’t widely available on the private market at a rate many homeowners, business owners and renters could afford. The program had a second mission, which is to reduce the nation’s overall flood risk through the development of floodplain management standards.

Attention has fallen on the increasing amount of money going to owners of properties that flood over and over, including those with large claims – so-called Severe Repetitive Loss Properties. FEMA’s official policy is to “eliminate or reduce the damage to property and disruption to life caused by repeated flooding of the same properties.”

It provides grants designed to reduce a community’s overall flood risk, for instance by helping pay to make stormwater drainage systems more robust, or buying out individual homeowners whose houses just shouldn’t be where they are because of intractable flood risk. The Natural Resources Defense Council, an environmental nonprofit, crunched the FEMA numbers and created an interactive map charting the mounting financial toll of severe recurring losses across the nation, county by county. The map is accompanied by a study titled “Losing Ground” that finds that the number of Severe Repetitive Loss Properties is increasing rather than decreasing.

It remains unclear why a relatively sparsely populated county like Escambia should have double the number of Severe Repetitive Loss Properties as a populous county like Miami Dade.

Underhill offered his thoughts.

“We’re pretty much the double-yellow line in Hurricane Alley,” he said. “We’re right in the center of the Gulf of Mexico. If you look at how the large weather patterns work, they pretty much suck hurricanes right into this hole.”