Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared on FloodTrends.org. Flood Trends has since merged with Flood Defenders to form Flood Defenders News.

In 2014, a freak rainstorm dropped almost two feet of water on Florida’s Escambia County in little more than a day. Whole neighborhoods were inundated. Roads and bridges washed out. A dam burst, requiring people to be rescued from rooftops. The basement of the county jail filled with water causing a gas explosion that killed two inmates.

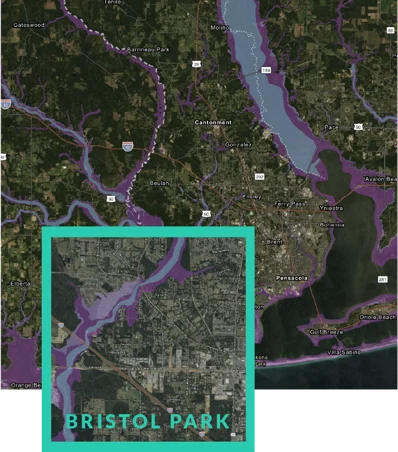

Escambia County floods in 2014. Credit: Jeremy Cooper

The flooding traumatized Florida’s oldest county, perched at the far-western edge of the state’s panhandle.

Dominated by Naval Air Station Pensacola, the county is renowned for its white-sand beaches and the emerald waters of Pensacola Bay.

As often happens when catastrophe strikes, the county rallied and remedies appeared to be on the horizon. With broad public support, county leaders laid out an ambitious agenda of 228 stormwater drainage projects bearing a staggering price tag of $417 million. Such networks of ponds and pipes either store runoff or divert it too lakes, streams and rivers and away from schools, churches and homes.

“We were very optimistic,” recalled Mary Gutierrez, who chaired the Stormwater Advisory Team (SWAT), which came up with the county’s list of 228 projects and a separate list for its largest city, Pensacola. “We were excited about the city and the county partnering on this and addressing the issues that occurred from that particular rain event. We had such community support, and it was very positive and a good step in the right direction.”

5 YEARS LATER:

7 PROJECTS AND A HURRICANE

That was in 2015. Five years later, only seven (3%) of the 228 county projects have been completed, although parts of some projects have been done. For the most part, however, the ambitions and hope reflected in the SWAT report collided with the cold reality that after a natural disaster the shared sense of loss and vulnerability fades quickly.

That cost might as well be in the billions as millions. Other than substantially raising local taxes or issuing bonds – both tough political and fiscal lifts – Escambia has little prospect of coming up with a quick $417 million. Even if it could, some of the projects require buying out homeowners, conducting environmental studies and waiting on approvals, all of which take years.

There was a huge public outcry and it could be that (the county engineers) were overzealous in what they were identifying and what they hoped they were going to accomplish,” said Gutierrez, an environmental scientist specializing in wetlands protection. “And then, obviously, all of that comes down to money. Where’s that money going to come from? Are you going to have to take that money from some other projects? ”

MARY GUTIERREZ

STORMWATER ADVISORY TEAM CHAIR

The county has spent about $40 million on drainage projects since 2014. Some money has come from state and federal grants, but one of the primary sources of funds is $4 million a year drawn from a temporary county sales tax that voters will need to extend in 2028, and every 10 years thereafter.

That makes coming up with $417 million difficult but not impossible. In the past six years, Escambia has raised nearly $150 million dollars — far more than has been invested in the flood protection plan — to rebuild the jail damaged in the 2014 flood event. The county successfully raised that money from three separate places: $20 million from the federal government, $50 million of the county’s own money from the Local Option Sales Tax fund and $80 million from investors in exchange for the county’s share of a statewide, half-cent tourism tax.

Escambia County’s flood dilemma underscores a challenge facing many of Florida’s 67 counties, and metropolises like Jacksonville, Miami and Tampa. The threats – and urgency for expensive action – will only increase in the years ahead.

As intense rain events become more common and sea levels rise, stormwater systems around the state are becoming overmatched.

To be sure, the county imposed tougher building standards after the 2014 flooding, requiring new buildings and subdivisions to be engineered to withstand more intense rainfall.

While the 2014 storm, with its 20 inches of rain, was considered a 100-year weather event – meaning there’s one chance in 100 of it happening in any given year – a storm of similar magnitude struck Escambia County a mere six years later.

In September, Hurricane Sally dropped two feet of rain on the county.

Predictably, places where stormwater projects had been completed fared much better than in 2014, areas like Beach Haven and Warrington. The installation of curbs, gutters and underground piping did the trick of moving vast quantities of rushing water away from vulnerable homes.

But there just weren’t enough of those places. Once again, the county suffered widespread stormwater flooding. This time, it and a storm surge caused more than $300 million in damage. The damage from Hurricane Sally alone was 75 percent of the price tag for the county’s entire 2015 stormwater improvement list.

NATURE DISREGARDS FLOOD MAPS

Spencer Blomquist lives in the city of Cantonment, a suburb north of Pensacola. He bought a house in a new subdivision in 2007, at a time when developers were building them feverishly across the nation during the run-up to the 2007 housing collapse.

His subdivision and several others were built on low-lying land along Eleven Mile Creek. Known today as Bristol Park, Bristol Creek and Ashbury Hills, the area is the focus of one of the costliest set of projects in the 2015 SWAT report. Ironically, the plan in the report was first conceived – but never implemented – back in the 1990s, before many of these houses existed.

Long before the subdivisions went in, county stormwater officials knew the area was flood-prone, based on basin studies done in 1994 and 1999, and previous flooding there, including during Hurricane Georges in 1998.

But the county had no way to fund the projects, including building 11 large stormwater retention ponds and widening of the creek so that it could hold more runoff during heavy rains.

Then, in the early 2000s, came the housing construction boom. Faulty FEMA maps showed the area as being outside a floodplain. Based on the maps, the county allowed builders to put in the new subdivisions, including the one in which Blomquist now lives.

When Blomquist bought the house, the builder assured him he wouldn’t need flood insurance because the new subdivision wasn’t in a flood zone. Blomquist wasn’t told that two creeks merge just upstream from his neighborhood, making it a natural flood basin. Nor was he told about the poorly maintained dam upstream.

The dam failed during the heavy rains in 2014, flooding Blomquist’s neighborhood and filling his house with four feet of water within 30 minutes.

A quadriplegic, Blomquist was alarmed enough by the incident to keep a fully inflated life raft in his garage.

“I knew I wasn’t going to be able to swim out,” he said.

In 2020, the dam was no longer a factor but the creek flooding from Sally filled his house with a foot and a half of water. There was no need for the life raft. But, once again, he was forced from his home while extensive repairs were made.

The house, which Blomquist bought for $257,000 14 years ago, has now generated about $400,000 in flood losses, he said. It was one of 160 in the neighborhood that flooded in 2014 – one of 70 during Sally.

The county really did not do any of the stuff for drainage that they should have as far as the creek goes. It probably wasn’t the best place for the county to approve development. People who have lived on the higher side of our neighborhood for twenty-some years said that when they moved there all the land where we are was swamp and wetlands. It seems crazy that the county allowed them to build that property. ”

SPENCER BLOMQUIST

BRISTOL PARK CITIZEN

“SCARY AS HELL”

Resident Jenifer Prevatte agrees.

In 2010, she, her husband and two children built a house along Eleven Mile Creek. Like Blomquist, they were told they didn’t need to worry about floods or flood insurance.

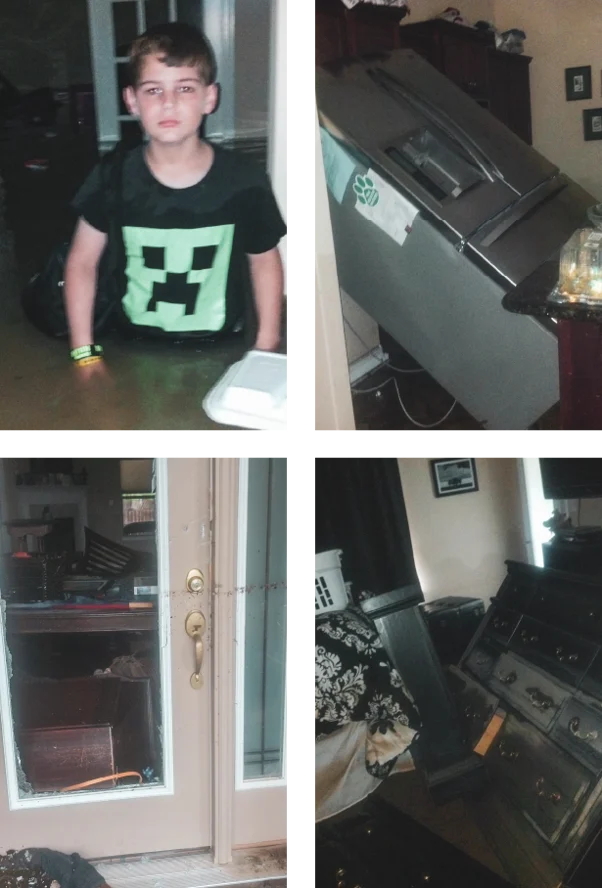

On April 29, 2014, heavy rains fell. At about 10:30 pm, the dam upstream failed. Water began gushing into the Prevattes’ house through the floors.

The rescue boat that came for them fought a vicious current, getting sucked away from the house and having to make a second approach. One by one, family members had to duck underwater to squeeze through a window and into the torrent outside, where they were hauled into the rescue boat against the backdrop of near-constant lightning strikes.

“It was scary as hell,” she said.

WHAT ESCAMBIA HAS (NOT) DONE

A year after the 2014 flooding, when the county created its $417 million list of 228 stormwater management projects, the Eleven Mile Creek plan from the 1990s was incorporated. Three of the 228 projects were devoted to fixing Eleven Mile Creek at a combined cost of $54 million. Just as in the 1990s, the plan consisted of building large water storage ponds, buying out homeowners and widening the creek. And just as in the ‘90s, the county still doesn’t have the money.

What the county has done since 2014 is use a $6 million grant from FEMA to buy out 17 homes along the creek and demolish them. Seventeen was all the grant would cover. Those empty lots are scattered among a greater number of still-occupied homes. Therefore, bulldozing the creek to widen its bed is a long way off. Nor has construction of the regional storage ponds happened. Design work for one – the West Roberts Road pond – is almost complete.

After Hurricane Sally, history repeated: Politicians once again touted long-promised grants they’d previously assured flood victims were in the works to continue the project. But nothing in the pipeline comes close to the roughly $50 million it will take to buy out additional properties, widen the creek, build the retention ponds and other work needed to avert future flooding in the flood-prone cluster of subdivisions where Blomquist lives. Financially, the only option is to do the project piecemeal. But it won’t be effective against flooding until the entire project is completed.

“Acquisition of the parcels and demolition of homes along Eleven Mile Creek will not in and of itself address the flood issues,” Matt Posner, interim director of the Pensacola & Perdido Bays Estuary Program, wrote in response to a question from Flood Trends. “Rather the suite of larger projects will all have to work in conjunction to address the problem.”

Nor have local politicians, including Steven Barry, the county commissioner for the area, provided a frank assessment that the area will likely remain flood-prone for the foreseeable future.

After Sally’s floodwater had barely receded, Barry reassured homeowners that he had submitted requests in 2016 to fund two flood-control projects from money available through the trust fund created to settle claims against BP stemming from the Deepwater Horizon oil spill.

“Both projects I submitted impact the creek and will improve stormwater management in the area greatly, one for creek restoration and one for additional retention pond construction,” he said in published comments. “Both projects have also received preliminary approval from the U.S. Department of Treasury, which is the agency overseeing the county’s expenditures of the BP RESTORE dollars, but we haven’t got final approval to begin the projects yet.” What Barry didn’t explain is that those grants are for design work — not construction.

“We are in the design phase,” said Barry aide Dawn Troche. “We are not close to construction yet.”

Blomquist and many of his neighbors see the situation as hopeless.

I think the neighborhood should just be knocked down and condemned because it’s always going to be a future issue with the creek running back there, especially with the significant rainstorms we have here and the pace of development. ”

SPENCER BLOMQUIST

BRISTOL PARK CITIZEN

FUNDING THE PLAN

Until recently, Chris Curb was the stormwater engineering manager for Escambia County.

“Problems like this, you don’t fix overnight,” he said. “It takes years to purchase property, to build regional ponds and for stream and floodplain restoration. The only time stormwater is sexy is right after a storm event like Hurricane Sally or April 2014.”

Doug Underhill, a Navy intelligence officer and county commissioner, said a bigger local investment is necessary to win state and federal grants.

If you go to Tallahassee with an empty hat, you will come home with an empty hat. If you go there asking for $10 million, you have to show up with a million in the hat because Tallahassee is not going to fund the first million dollars of any project. They want to see that the local government cares enough about it to put our own money where our mouth is. Otherwise, we’re just making a childish ask. ”

DOUG UNDERHILL

ESCAMBIA COUNTY COMMISSIONER

The cold, hard reality of funding will always be a stumbling block to drainage projects. Raising taxes and wrangling grants from Tallahassee or Washington will continue to be competitive challenges for Escambia and other Florida counties. Pressure to build subdivisions will continue, and there’s no quick fix for rainfall intensification across the southeastern United States.

Meanwhile, homeowners like Blomquist and Prevatte are facing endless nightmares in homes that seem destined to flood every few years, and the National Flood Insurance Program continues to hemorrhage billions of dollars paying to repair the same homes, over and over.

The Prevatte family’s harrowing nighttime rescue in 2014 is something they’ll never forget. By contrast, when Hurricane Sally dropped two feet of rain in September, their house filled more slowly, never rising above two feet.

While not as terrifying, the flooding from Sally still turned her life upside down.

The neighborhood needs to be condemned, Prevatte said.

“Nobody should live here,” she added.

Credit: Jenifer Prevatte